Six Lives of WW1. Based on real people and events, Six Lives is a fictional view of the war through the lives of six individuals related through, family, friendship or circumstance. The war destroyed lives and left families bereft but also necessity led to women experiencing work in men’s roles and the widening of women’s suffrage. Click on the stories above for a small sense of the many different experiences of World War One.

Private Charlie McTaggart. Charlie McTaggart from Lochee, Dundee, was 22 at the outbreak of WW1. He was an assistant overseer at Cox’s Mill and had a good career ahead of him. Engaged to his childhood sweetheart Morag, life felt good for Charlie but the call to defend his country was about to change Charlie’s life forever. Read on to learn about Charlie’s war…

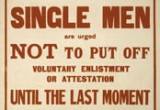

Charlie enlists. Spurred on by Lord Kitchener calling men to war, Charlie was among the first in Dundee to enlist. He had expected his older brother John to enlist with him but much to his surprise he declared himself against the war and said he had no intention of ever signing-up.

Farewell Dundee. Charlie took part in the great farewell march from Dudhope Castle to Tay Bridge Station. There the men gathered bound for Southampton where they boarded the S.S. Rossetti at Southampton for France. Spirits were high and for many it seemed like the start of a great boys’ adventure. Most thought it would all be over in a few months.

Into battle. Charlie’s first taste of battle was at Neuve Chapelle. It was a total test of his nerve and training. Advancing into machine gun fire, Charlie felt the bullets splitting the air around him but miraculously was not hit. By the end of 4 days fighting there were 13,000 casualties.

A letter home. Letters home were strictly monitored to control the information leaking from the front. Charlie’s few words to his fiancé hide little of what he was feeling. “My Dearest Morag, if the good that comes from me being here is to save you from seeing what I have seen then I am proud to be here.”

Wounded at Aubers Ridge. In battle at Aubers Ridge Charlie was injured by a bullet through his arm. Missing bone and arteries, the injury was relatively minor but turned life threatening when infection set in. There were no antibiotics in 1915 and so the infected flesh was cut away and carbolic lotion applied to clean the wound. The infection subsided and Charlie was ordered home to convalesce.

Brothers fight. Charlie hadn’t seen his brother John since he left for the front in September 1914. Visiting him in July it was clear that John hadn’t changed his views on the war and that he was now an active member of the No Conscription Fellowship (NCF). Charlie hated the war but couldn’t forgive John for the shame he was bringing on the family. Charlie vowed never to speak to his brother again.

Returning to the front. After a long convalescence, Charlie was again fit to return to the front. He was reunited with his pals in Dundee’s Own but there were some missing faces along with many new ones. Charlie had grown hardened to the inevitable losses but he still found comfort in the camaraderie of the men. Falling back into the routine of life at the front Charlie received a letter from Morag. John was to appear before the Dundee Military Tribunal and would likely go to prison for refusing military service. Charlie ignored the letter, still angry with his brother and angry with Morag for admiring John’s courage.

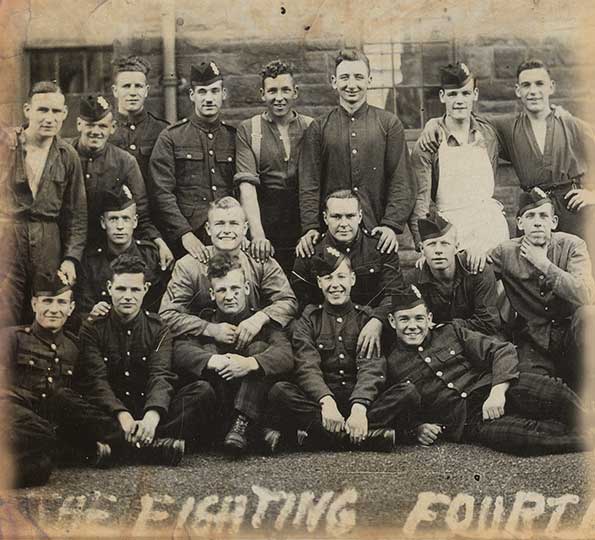

The Battle of Loos. Charlie returned to the ranks of the 4th Black Watch in time to take part in the Battle of Loos. The fighting was the bloodiest he had witnessed. As soon as Charlie had mounted the parapet he knew his unit was in trouble. Many fell barely yards from their line, brought down by relentless machine gun fire. By the end of the battle there were over 60,000 British casualties. Charlie’s unit, Dundee’s Own, was decimated with 19 officers and 230 men killed or wounded. Charlie pictured his parents and Morag dreading bad news like so many others in Dundee would receive.

La Basse. Following the Battle of Loos the 4th Black Watch (Dundee’s Own), was amalgamated with the 5th Angus Battalion of the Black Watch. Promoted to Sergeant, Charlie led a group of men on a night trench raid at La Basse. Requiring stealth and bravery, trench raids often involved vicious hand-to-hand combat. Charlie’s men had a good night, killing 5 Germans without any losses of their own.

Back to Blighty. Charlie was sent back to Britain to train men in bombing techniques. His trainees were often the same age as him and yet his experiences of the last year had left Charlie feeling so much older than them. Bombers had a reputation as the toughest men in a battalion and so Charlie was determined to turn his recruits into soldiers that were not only tough but were absolutely ready for war.

Charlie thinks of his brother. Charlie heard from his fiancé that his brother John was to appear again in front of the Dundee Military Tribunal for refusing to sign up. As much as Charlie missed his brother he still could not find it in himself to understand his brother’s views no matter how highly Morag spoke of him. Charlie resolved again to put John out of his mind.

On leave Dundee. Early in October Charlie received a letter from his Mother telling him that his father had signed up. She explained he was doing it to take Johns place at the front although she suspected he would have eventually signed up no matter what. Charlie had seen families destroyed by the war; the thought that his mother might lose a son and her husband weighed heavily on him. He feared the worst for his father and needed to see him in person, to hold his hand possibly for the last time. Charlie was overdue leave and made arrangements to travel immediately. He would surprise Morag at the same time.

Bravery off the battlefield. Charlie returned to France but while delivering supplies to a clearing station he gave blood to a wounded man in a person-to-person transfusion. It was a dangerous procedure, which saved the man’s life but left Charlie weak. He returned home for three weeks’ special recovery. While recovering a letter arrived from his mother to tell him his father had been injured in battle, losing part of his leg. Charlie was shocked but had seen enough terrible injuries to be thankful it was not worse. Hopefully he would be able to go back to teaching. Most invalided soldiers would be less fortunate.

A deadlier enemy arrives. Back home, Charlie was among the first to contract Spanish Flu. He was up against a deadly enemy but true to form he dodged one last bullet and recovered. Capable of killing in 24 hours, Spanish Flu was the sting in the tail of WW1. Carried home by soldiers, a pandemic ensued killing 50-100 million people worldwide, far more than the 17 million deaths of WW1.

Hope in Charlie’s heart. While recovering Charlie wondered if the flu would take his conscientious objector brother. A nurse caring for Charlie told him during his fever he had mumbled peoples names and said something that sounded like, ‘brave John’. He later learned that few men in prison caught the flu due to them having little contact with the outside. He shook his head at the thought of referring to John as ‘brave’ but he couldn’t deny feeling some relief that John was probably safe in prison.

Armistice. Charlie was thankful that he, his father and Morag’s dad Peter had survived the war with the news that it finally came to an end in France and Belgium at 11.00 am on the eleventh day of the eleventh month 1918. Elements of the German High Sea fleet surrender off Rosyth on 21 November. In December Allied troops enter Germany in the same month that David Lloyd George wins the general election to become prime Minister of the National Government.

New Beginnings. With Morag’s father safely home from the front, Morag and Charlie finally got married. To Charlie, Morag was the most amazing women in the world. In September 1914 she had promised him they would have their life together. He often thought she had promised too much. He watched and marvelled that day as his father and others locked in a lively but peaceful political discussion with John, while others gossiped and danced, just happy to be having fun. Charlie caught the eye of Morag, looked skyward, raised a glass in memory of his fallen pals and whispered to her – “new beginnings”.

Private Charlie McTaggart

August 1914

Charlie enlists

September 1914

Farewell Dundee

March 1915

Into battle

April 1915

A letter home

May 1915

Wounded at Aubers Ridge

July 1915

Brothers fight

September 1915

Returning to the front

September 1915

The Battle of Loos

June 1916

La Basse

September 1916

Back to Blighty

September 1916

Charlie thinks of his brother

October 1916

On leave Dundee

August 1918

Bravery off the battlefield

September 1918

A deadlier enemy arrives

September 1918

Hope in Charlie’s heart

November 1918

Armistice

May 1919

New Beginnings

Lieutenant Martin Coulter. At the start of World War One, 23 year old Martin Coulter from Dundee was in the Royal Navy and had just been commissioned as a lieutenant on the battlecruiser HMS Inflexible in the Mediterranean. Martin’s interest in the navy started as a child when he visited the training ship HMS Unicorn in Dundee. Aged 8 at the time, Martin was on a day out with his friend Charlie McTaggart. Read on to learn about Martin’s war…

Battle of Coronel. On 1st November 1914 Von Spee’s squadron, SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau along with 3 cruisers had encountered and destroyed a British squadron of ships killing some 1,600 men including Rear Admiral Cradock. HMS Inflexible, Martin’s ship, and Invincible were sent to hunt down Von Spee’s squadron.

Battle of the Falklands. The enemy ships were sighted off the Falklands and the powerful battlecruisers quickly closed the gap on the German ships to 14 km. At 13:20 Martin felt the ship vibrate to the report of the 12-inch guns as they fired on the SMS Gneisenau. By 16:20 the battle was over and Spee’s entire squadron lay at the bottom of the sea. 2,200 German sailors were killed in the encounter.

Repairs at Gibraltar. Following repairs at Gibraltar, Inflexible returned to the Mediterranean as flagship of the Royal Navy’ Mediterranean Fleet where she was involved in the bombardment of the Dardanelles forts on 19 February.

Inflexible beached. On 18 March, Inflexible was in the first line of ships sent into The Narrows to clear the way into the Sea of Marmora, and hence to Constantinople. Hit by Ottoman artillery, Inflexible suffered several casualties and was eventually beached after running into a mine.

HMS Warspite. In April 1915 Martin transferred to the battleship HMS Warspite. Armed with 8 x 15 inch guns and capable of 24 knots, the 33,000 ton ship was among the most powerful in the world. Martin was proud to be on board HMS Warspite and expected she would be called to sea within days but to his amazement the ship would spend much timed anchored at her base at Scapa Flow, Orkney.

Word from Charlie McTaggart. By August 1915 Martin was bored and frustrated as he and the rest of the Warspite crew lay in isolation at Scapa. So it was a welcome distraction to receive a letter from his friend Charlie. Charlie’s news of being wounded and nearly loosing his arm brought it home to Martin how the war was stripping people of family and friends.

Bad luck and accidents. Having just returned to service after running aground in the River Forth, Warspite suffered further damage when she collided with her sister ship HMS Barham. A superior officer overheard Martin blaming the Captain and he narrowly escaped a charge. After repairs the Warspite rejoined the Grand Fleet on Christmas Eve.

Bombardment of Lowestoft. Following the bombardment of Lowestoft the 5th Battle Squadron was sent to Rosyth to support the Battlecruiser Fleet, which included Martin’s old ship the Inflexible as part of Rear Admiral Hood’s 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron.

Intelligence intercepted. In late May, the Admiralty intercepted and deciphered messages which suggested that the whole of the German High Seas Fleet was going to be at sea to support another raid. The Grand Fleet was ordered to sea. Martin’s ship the Warspite was ready.

The Battle of Jutland – into battle. Martin was heading into what would become the biggest naval encounter between Britain and Germany of the war. The Battle of Jutland began around 14:30 on the 31st May but because of a signalling error the Warspite was trailing behind and Martin could only watch as first the Indefatigable and then the Queen Mary blew up. As they headed into the battle they scored a direct hit on the SMS Von der Tann, the German battlecruiser responsible for destroying the Indefatigable.

The Battle of Jutland – a sitting duck. When the rest of the High Seas Fleet was sighted, the Squadron steamed past the retiring battlecruisers to engage the enemy. Warspite was hit by a shell, jamming her steering. She was a sitting duck as she turned two complete circles. Martin thought his ship was finished but despite being hit 13 times she stayed afloat allowing time for the ship’s engineers to free the steering but in doing so placed them on course for the German Fleet.

The Battle of Jutland – escape. As the ship steamed back towards the German Fleet reports of damage to the ship revealed she was in a bad shape. Only one gun turret was operational but damaged rangefinder equipment meant 12 salvos fell short of their target. The captain ordered the ship to be completely stopped for 10 minutes while further repairs were made to the steering. The decision paid off and as the light faded she turned away back towards Rosyth.

Convoy duty. In April 1917, 874,140 tons of shipping travelling to and from Britain was lost to U-boats. Martin, now a lieutenant on a destroyer, he spent 9 months in the Eastern Atlantic assigned to the convoy system escorting merchant ships. In June 1917 he wrote an upbeat note to his friend Charlie McTaggart, “Protecting ships carrying food to our families is the most satisfying work of my career”.

Old friends meet again. While on leave in December 1918, Martin returned home to see his old friend Charlie McTaggart. Promoted to Lieutenant Commander, Martin was looking forward to a long peacetime career at sea but Charlie had no similar ambition to remain in the forces. Despite their different lives the two men remained close friends until Martin died when his ship HMS Royal Oak was torpedoed and sank by a German U-boat while anchored in Scapa Flow on 14 October 1939.

Lieutenant Martin Coulter

November 1914

Battle of Coronel

December 1914

Battle of the Falklands

February 1915

Repairs at Gibraltar

March 1915

Inflexible beached

April 1915

HMS Warspite

August 1915

Word from Charlie McTaggart

December 1915

Bad luck and accidents

April 1916

Bombardment of Lowestoft

May 1916

Intelligence intercepted

May 1916

The Battle of Jutland – into battle

May 1916

The Battle of Jutland – a sitting duck

May 1916

The Battle of Jutland – escape

May 1917

Convoy duty

December 1918

Old friends meet again

Mother – Elizabeth McTaggart. Elizabeth McTaggart was a housewife and the mother to two grown-up sons, Charlie (24), and John (28). Elizabeth felt happy in the summer of 1914. Charlie was engaged and John was married with 2 children. Her husband, James McTagart, taught English at The High School of Dundee. Compared to many, life was comfortable. Everything was about to change. Read on to learn about Elizabeth’s war…

Sons at odds with each other. At the outbreak of the war Charlie was among the first to sign up but John was opposed to the war and refused to enlist alongside his brother. Elizabeth expected John would change his mind out of guilt but was surprised by her relief that at least for now John would be safe.

Caught in the middle. Nearly a month had passed since Charlie left for the front and since then Elizabeth had felt increasingly lonely and isolated. James her husband talked of enlisting and had also fallen out with John who had declared himself against the war. As a mother and a wife, she was caught in the middle.

Charlie writes but hides the truth. “Mum, sorry I’ve taken so long to write. I expect you’ve been worried but to be honest things have been pretty quiet here. We only spend a few days at a time in the trenches. Last week I was part of push and myself and few other lads went on a scouting expedition 2 days before an attack. I was scared but with good lads around me I felt safe enough. Keep sending the fruit cake. Love, Charlie.”

Charlie wounded. Just a few months after Charlie’s reassuring letter, Elizabeth receives news that he was injured in battle at Aubers Ridge and that he is seriously ill with an infection. She knew an infection could kill him as easily as a bullet. Since the day Charlie left she had lived in fear of the dreaded official War Office Telegram to notify her that Charlie was either dead or missing presumed dead. While he was fighting for his life there was hope.

James is appalled by his son. Elizabeth hears that Charlie survived the infection and will be moved to England to convalesce. She arranges a family evening to celebrate only for it to be wrecked by James and John arguing. John swears he can convince Charlie to desert. James had learnt that day of eight of his old pupils dying in battle and in a blind rage told John he was an outright a coward.

A gift through the post. Elizabeth was hoping for a letter from Charlie in the morning post. Her hope was quickly displaced by fury when out of an envelope fell two white feathers. Inside a note read: ‘TWO COWARDS IN THE FAMILY – YOU MUST BE A PROUD MOTHER AND WIFE’. She burned the letter and feathers but wondered how many people felt the same about her family.

James signs-up. As expected, John is arrested for refusing to sign-up for military service and despite his protestations is charged and sentenced to six months hard labour. The story is published in the morning paper and James feels nothing but shame. Elizabeth tries to defend her son and to change his mind but James dismisses her pleas and proclaims he’ll take John’s place at the front. He leaves the house and returns 3 hours later as a recruit and with a date to start training.

Charlie home on leave. The day James signed-up, Elizabeth wrote to Charlie. Less than a week later Charlie was at the door. Charlie looked well. He was currently based in England training men in the use of explosives. She was overjoyed to see him. James was working his last few days at the school and so during the day she and Charlie worked to prepare a meal out of what they could. Charlie had friends in the country. He took off on a neighbour’s rusting bike and by the early afternoon he was back with enough rabbit for a banquet. That evening James came home to the smell of stew and sound of laughter in the kitchen. Seeing Charlie was a real tonic and the two of them talked and drank into the early hours.

James leaves for France. Elizabeth came to terms with James joining the war. Since signing up, their relationship had somehow improved. James seemed relieved. He was once again proud; a quality about him that had somewhat disappeared since men began leaving for the front. She truly appreciated the pressure men were under to fight. They spent Christmas 1916 together and on January 7, 1917 she waved him goodbye from Tay Bridge Station.

Time to get busy. Before marrying, Elizabeth worked in a bank as a clerk. She enjoyed her work and had considered applying to work at a bank in London. As was common at the time, when women married they were often barred from employment in certain rolls. Elizabeth had enjoyed her independence but James didn’t want her to work and so dutifully she followed his wishes. But with men away at war and money short because of rising prices Elizabeth had no option but to seek work. Secretly she felt quite liberated at the opportunity.

No to munitions. There was plenty of work in the local munitions factory but Charlie’s fiancé, Morag, had worked there and told Elizabeth about the women suffering with TNT poisoning. And in January 1917, 73 people were killed in an explosion at a London munitions factory. She could join Morag in the Women’s Land Army but instead decided on a far bigger idea – she would apply to join the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

Stationed in France. Elizabeth wrote to James with news that she had joined the WAACs. As she expected he was angry but the war had given opportunity to women and empowered them to step in to male roles. She was lonely in Dundee and tired of hearing news of fallen men. Her experience working in the bank gained her a job as a clerk in a motor transport depot in Abbeville. Along with other women she helped coordinate the movement of thousands of vehicles along the front.

Nine dead. The depot at Abbeville was out of the reach of enemy guns but it was vulnerable to attack by air. On 30 May 1918 nine women died in an air raid. They were the first WAAC deaths on active service. Elizabeth escaped injury but one of her best friends was seriously injured. The whole camp was destroyed during the raid and Elizabeth helped pull survivors from the collapsed remains.

James injured. Following the attack on Abbeville Elizabeth was acutely aware of the reality of the war. She had seen dead bodies and people with life changing injuries. As much as the intensity of work at Abbeville had kept her occupied, since the attack she thought only of her husband James and her son Charlie. In June 1918, an officer brought her the news that James had been caught in machine gun fire. He had survived but had lost the lower half of his right leg and would soon be on a ship back to England.

Homeward bound. James would soon leave the military convalescence home and at the same time be discharged from the army. Without anyone to look after him Elizabeth was given leave to return home to be with him. The last letter she received in France was from Morag, Charlie’s fiancé telling her that Charlie was seriously ill with flu. As far as she knew Charlie could already be dead such was the deadliness of the virus. Her journey back to Dundee would take her 3 days.

War over. With the war over a new normality was taking shape in the McTaggart household. Charlie had survived the flu and James continued to adjust to his injury. The shared relief and understanding of each having survived the war gave them reason to put the war behind them. They had done everything and more than their country could ever have expected of them.

Forgiveness. Elizabeth had experienced the war first hand. She was angry at the men that had pressed them in to the conflict but believed Britain had no choice but to finish the job it had started. Her son John had spent 2 years 7 months in prison as a conscientious objector but would soon arrive home at Tay Bridge Train Station. At her side was John’s wife Rebekah and resting on his crutches was James. Despite the odds Elizabeth’s small family had survived the war and as John walked along the platform James held out his hand to welcome John home.

Mother – Elizabeth McTaggart

August 1914

Sons at odds with each other

October 1914

Caught in the middle

April 1915

Charlie writes but hides the truth

May 1915

Charlie wounded

July 1915

James is appalled by his son

March 1916

A gift through the post

October 1916

James signs-up

October 1916

Charlie home on leave

January 1917

James leaves for France

March 1917

Time to get busy

April 1917

No to munitions

November 1917

Stationed in France

May 1918

Nine dead

July 1918

James injured

September 1918

Homeward bound

December 1918

War over

April 1919

Forgiveness

Susan Brandon – Nurse. At the outbreak of war Susan Brandon, from Dundee, was working at St. Luke’s Hospital in Chicago but knowing there would be a need for nurses to treat injured soldiers she returned to Britain to join Queen Alexandria’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS). Read on to learn about Susan’s war…

Off to France – Villeneuve St. Georges. After a brief visit to her home in Fairmuir, Dundee, Susan was on her way to France and was posted not far from Paris at No. 3 Casualty Clearing Station operating at the railway junction of Villeneuve St. Georges. Casualty Clearing stations role was to provide primary treatment for the wounded and to prepare them for onward travel to base hospitals.

Gare Maritime – Boulogne. By March 1915 Susan was at a Stationary Hospital which had been created by converting sugar sheds on the Gare Maritime at Boulogne and where she dealt with the casualties from Neuve Chapelle and Aubers Ridge.

A familiar accent. Following the battle of Aubers Ridge injured men arrived at the hospital. Some could be stabilised but others were too weak to travel further. One day Susan came across a soldier with a Dundee accent. He’s was telling the men around him how he would be back at the front in no time but Susan knew from experience that the infection taking hold in the soldier’s wounded arm was potentially fatal.

Susan cares for Charlie McTaggart. Susan saw many men die from small wounds. She rarely saw a man with a bullet wound to the torso as those men tended to die on the battle field. Charlie McTaggart was the man with the Dundee accent. Susan took it upon herself to care for him. He quickly became seriously ill with the infected wound caused by a bullet carrying threads of his filthy tunic into his flesh.

No antibiotics. The infection in Charlie’s arm required urgent treatment. In a matter of hours, the only choice would have been amputation. The first option was to cut away the infected flesh and to apply carbolic lotion to the wound. Never had Susan imagined she would be witness to so many seriously injured and dying men.

The treatment. Charlie slipped into un-conscientiousness before the procedure to clean his wound and pack it with a dressing of carbolic lotion. He woke a day later still sick. While he slept Susan helped treat another 50 or so men. As he improved she would make time to stop by his bed to talk about Dundee. The familiarity of their conversation was a comforting distraction. Within a week, Charlie was on his way to the UK.

Transferred nearer to the front line. The need for experienced nurses nearer the front line was urgent and soon Susan found herself at Casualty Clearing Stations at Popinghe and then Baileull. She had become hardened to the war, none-the-less she knew the closer to the front she got, the more urgent and traumatic the work would be.

The fear of enemy attack. Although clear of the front line Susan could hear artillery fire and German Taube aircraft occasionally bombed nearby rail junctions and supply depots. But compared to the daily losses at the front nurses were relatively safe. Around 1500 nurses from several countries died during the war. Many died from disease although some did die from enemy action.

Leave. Nurses were rarely kept at a clearing station for longer than 6 months at a time. Susan was overdue a break and in January 1917 returned to Dundee for some well earned leave. She worked her passage by assisting on an ambulance train through to Dundee bringing seriously injured men home to Scotland. She was moved by the stories of bravery the men told and by how many of them were determined to return to the front

A face in the crowd. As she arrived at Tay Bridge Station she saw a large group of fresh looking, presumably new soldiers waiting to travel south. ‘How many men were left in Dundee’, she thought to herself’. Among the men she saw a mature man who reminded her of Charlie McTaggart.

The Ambulance Train. For the first part of 1917 Susan was posted to work on an Ambulance Train ferrying injured and sick men to base hospitals and the port. The train could carry as many as 500 patients, many of whom were either helpless or in a critical condition. Most of the men came aboard the train still in their uniforms. Much of the journey would involve continuing to treat the men including getting them out of their filthy uniforms.

Perilous conditions. Susan was drafted back to work in a Clearing Station. This time it felt as though the front was just yards away. Indeed during the German offensive of 1918 Clearing Stations and Base Hospitals often had to pack up and move back at very short notice under harassing artillery fire.

A direct hit. While working a long shift treating men arriving directly from battle, shells began to land closer and closer to the Clearing Station. Then it happened. A shell struck just yards from the treatment shed blowing a wide hole in a wall and sending shrapnel and debris in all directions. The air was thick with dust, the smell of explosives and burnt flesh.

Gallantry. As the dust settled, Susan’s ears were ringing, masking the screams of men and nurses. The Matron and a Sister were on the floor motionless. Another shell exploded less than a 100 feet away and the ground felt as though it lifted. Shrapnel ripped at the building and a piece grazed Susan’s leg. She crawled to the Matron and Sister and saw that the Matron was bleeding but still breathing.

Help arrives. Two more shells found their mark nearby but Susan stayed with the Matron and Sister. Susan saw that the sister was motionless; a scarlet patch now seeped through her uniform, she was dead. The Matron regained conscientiousness but was unable to move. For the next hour while the attack continued Susan did her best to treat the Matron while also doing what she could for others around her.

Military Medal for Bravery. Susan was awarded the Military Medal for her bravery; specifically for ‘bravery and devotion to duty during a hostile bombing raid’ when she ‘worked devotedly for many hours, under conditions of great danger’.

Susan Brandon – Nurse

December 1914

Off to France – Villeneuve St. Georges

March 1915

Gare Maritime – Boulogne

May 1915

A familiar accent

May 1915

Susan cares for Charlie McTaggart

May 1915

No antibiotics

May 1915

The treatment

January 1916

Transferred nearer to the front line

July 1916

The fear of enemy attack

January 1917

Leave

January 1917

A face in the crowd

May 1917

The Ambulance Train

April 1918

Perilous conditions

May 1918

A direct hit

May 1918

Gallantry

May 1918

Help arrives

June 1918

Military Medal for Bravery

John McTaggart – Conscientious Objector. John McTaggart was 26 and an insurance agent when war broke out. He was married to Rebekah, an Irish spinner at Cox’s mill in Lochee, and father to Michael and Joshua. John had a younger brother, Charlie, who joined the army just days after war was declared. Read on to learn about John’s war…

War on the horizon. John was politically minded and as well as being a trade unionist was a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). By 1912 John could see the shadow of war loom large over Europe and John along with fellow ILP delegates pledged to make every effort to prevent war breaking out across the continent. But when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated on 28th June 1914, John was certain war would follow within weeks.

Peace Demonstration. On August 9 1914, just days after war broke out John attended a Peace Demonstration at Glasgow Green. Those present depressingly realised ‘they could not stop the war’. They hoped at least to counter the jingoism and war fever sweeping over Europe and to encourage the Government to use every endeavour to restore peace.

No-Conscription Fellowship. While John’s brother Charlie underwent basic army training, in contrast John worked with a host of Dundee war resisters in the ILP and the British Socialist Party. This was national movement but Labour leader J. Bruce Glasier asserted that ‘Anti-War feeling in Scotland was much more energetic and aggressive than in English Branches’ of the ILP by January 1915.

You’re no brother of mine!. John got news that his brother Charlie was home convalescing after being injured in battle at Aubers Ridge. John went to see him believing Charlie might be willing to hear his opinions on the war. John was now an active member of the ILP and the No-Conscription Fellowship. To John’s dismay Charlie was not impressed and in the end asked for John to be escorted out. John left close to tears and Charlie screamed after him – “you’re no brother of mine!”

Conscription introduced. The Military Service Act introduced conscription on January 27 and on March 2nd all men of military age would be deemed enlisted. In Dundee city war resisters formed the Dundee Joint Committee Against Conscription and included Ewan Geddes Carr, Scottish Prohibitionist leader Edwin Scrymgeour, and Prohibitionist, Socialist and International protagonist, Bob Stewart.

John in front of Military Tribunal. John and his brother Charlie had spoken to each other only once since war broke out. In the meantime Charlie had come through action at Loos in September 1915 and La Bassee in June 1916. Charlie was sent back home after the battle of Beaumont-Hammel and the Schwaben redoubt in September that year just as John was making his first appearance before the local Military Tribunal and Tribunal chairman Alexander Spence.

6 months hard labour. John claimed exemption from military service because he was politically opposed to the war. His application was rejected as was his appeal and in October 1916 he was finally arrested, charged and sentenced to six months hard labour for refusing military service.

Objectors together. John served his sentence in a variety of places including holding cells at Dudhope Castle Military Barracks, Bell Street Police Station Dundee and Hamilton Prison before arriving at Ballachulish Road Camp in Argyll. He was in the company of a dozen Dundee and 200 other conscientious objectors including leading activist James Maxton, Ewan Carr and James Sangster.

Released and re-arrested. John was released on January 22, 1917 but was immediately taken back into police custody and stood before the court once more. Again, he refused military service and this time was given a one-year prison sentence and was returned to Ballachulish camp to begin his second term in incarceration.

Wakefield Prison Work Camp. Ballachulish road camp in officially closed in June 1917 to be converted into a German prisoner of war camp. John had by that time been transferred with many of his fellow camp inmates – and most of his fellow Dundee COs and ILP/NCF comrades – to Wakefield Work Centre to complete his sentence.

A book of names. While at Wakefield John began an autograph book. Therein, he kept messages and entries from COs from across Britain who would write a political note or make a philosophical or ideological statement in defence of their anti-war views. In most cases the COs also listed the detention centres where they found themselves incarcerated.

Life for John’s wife and family. Rebekah agreed with her husband’s views but like other wives of Conscientious Objectors, life was difficult. They had the support of the Dundee Joint Committee Against Conscription which held regular meetings voicing their opposition to war, highlighting conscription issues and abuses, while maintaining public awareness of the plight of COs across the country. They provided much needed financial support for all the dependents of Dundee COs.

A further 2 years. John remained in Wakefield until his next release date in January 1918. Upon his release, he was once again rearrested and on this his third court martial was sentenced to a further two years in prison for refusing military service. He returned to Wakefield Prison and served some of his time at Wormwood Scrubs.

Moved to Wormwood Scrubs. John’s brother Charlie returned from the front in September 1918 and remained in Dundee after contracting and recovering from Spanish Flu. Charlie’s war was over. But John’s war resistance continued and incarcerated in Wormwood Scrubs he would was to serve out the remainder of his two-year sentence. After the Armistice in November he successfully applied to return to Scotland to serve out his time.

Released from prison. John was finally released from prison along with fellow Dundee absolutist Bob Stewart in April 1919 after serving two years and seven months. His health had suffered considerably as a result but like his brother Charlie he had survived his ordeal as too had 90 other Dundee COs and their families.

Forgiven. John felt proud of his achievements and had even managed to make things good with his brother. Considering him a coward John’s father signed after the third military service was passed in April 1918 (setting the upper age limit at 51). He claimed he was taking John’s place at the front. He lost part of his leg at the Battle of Selle in October. In May 1919 the family were reunited and his father forgave him recognising his son’s commitment. Dundee had many conscientious objectors and similar tales of reconciliation were now more common across the city.

Praise from across Scotland. Following the war Dundee’s war resisters and COs came in for special praise from across Scotland. Even before hostilities had ceased the ILP reported that the city’s war resisters and objectors had ‘steadfastly and fearlessly fought for liberty and Socialism’ and thus ‘had its sons in every prison and penal centre set apart for conscientious objectors to militarism.’ In the great inevitable political uprising … destined to place Labour permanently in power the working class of Dundee will demand a foremost a place.’

General Election success. John was part of an influential radical left wing movement to emerge in Dundee in the 1920s, which was ultimately responsible for the election of two anti-war pacifists, E.D. Morel and Edwin Scrymgeour, in the 1922 General Election. On that day the McTaggart family also celebrated their part in Morel and Scrymgeour’s General Election victory in Dundee. Churchill left the city defeated and old wounds began to heal.

John McTaggart – Conscientious Objector

June 1912

War on the horizon

August 1914

Peace Demonstration

January 1915

No-Conscription Fellowship

July 1915

You’re no brother of mine!

January 1916

Conscription introduced

September 1916

John in front of Military Tribunal

October 1916

6 months hard labour

October 1916

Objectors together

January 1917

Released and re-arrested

June 1917

Wakefield Prison Work Camp

August 1917

A book of names

November 1917

Life for John’s wife and family

January 1918

A further 2 years

September 1918

Moved to Wormwood Scrubs

April 1919

Released from prison

May 1919

Forgiven

June 1919

Praise from across Scotland

November 1922

General Election success

Fiancée – Morag Anderson. Morag got engaged to Charlie McTaggart in June 1914. She was just 15 when she first met Charlie. On the order of his mother, Charlie was on his way to the barbers but would rather have been out with his pals. Morag caught his eye as they rode the tram and something clicked between them. Read on to learn about Morag’s war…

Morag faces reality. The day Lord Kitchener called men to war Morag knew Charlie would sign up. For Morag though it was not just the fear of losing her fiancé, it was also her own dream to study for a degree that was in doubt. Few women studied for degrees at the time and what with her brothers also going to war, she would be expected to work.

A short goodbye. On a warm September morning Morag said goodbye to Charlie. She should have followed him down to Tay Bridge Station along with many others lining the route of the farewell march. She wanted her farewell to be just between them, not shared with thousands. She told Charlie he would be back and that they would have their life.

Charlie writes. “… if the good that comes from me being here is to save you from seeing what I have seen then I am proud to be here. Charlie” Morag wondered what kind of a man would come home. She felt for all the men and their families and with guilt wished Charlie had the same views as his brother John who refused to fight.

Charlie injured. Morag receives word that Charlie has been injured but is recovering and has been transferred to a military convalescence hospital in the south of England. Morag’s happy he’s safe but she cannot afford the train fair to see him.

Munitions work. Against Morag’s internal wishes she took up employment at the Dundee National Shell Factory. Such factories were opening all over the UK in response to the ‘Shell Crisis’ declared earlier in the year. Her family needed the money and as much as she was now against the war she hadn’t the courage to voice her opinion.

Brothers fall at Loos. Morag’s brothers Stuart and Angus had volunteered around the same time as Charlie. With them all away she learnt to expect bad news. In late September 1915, her family heard Stuart was missing presumed dead. Just 18 years old, Stuart was Morag’s baby brother. A day later Angus too was reported missing. Both had fallen at Loos; their bodies were never recovered.

Dundee Rent Strikes. While men were away fighting and those left at home struggled to make a living, the many private landlords of Scotland imposed rent rises. By now Morag’s anger was boiling over and the injustice of the rent increases spurred her into action. With the encouragement of Charlie’s brother John, Morag put herself at the heart of the Rent Strikes.

The Bellefield Avenue barricade. Morag helped Dundee tenants organised protests to highlight the insensitivity of the rent rises. Such was her feeling that she helped residents of a tenement in Bellefield Avenue to erect barricades to block landlords. Dundee’s rent strike was the second largest in Scotland. The strike ended when Parliament passed the Rent Restriction Act in November.

Tired of munitions. The munitions factory was busier than ever but Morag couldn’t square in her mind what she was doing. Often, she thought, “maybe this shell will save Charlie but what of the men that would lose their lives as if by my own hand?” Morag wanted to be useful but not by aiding death.

Morag writes to Charlie about his brother John. “My Dearest Charlie, I just thought you should know that John is to stand before the Dundee Military Tribunal. He’ll likely go to prison for refusing to sign up. I’m so proud of you Charlie for what you are doing. I’m also proud of John for standing by his beliefs. He helped me during the Rent Strikes and listening to him speak I wouldn’t be surprised if one day he goes into politics.”

A surprise at the factory gates. Another long shift over, Morag wrapped up warm and walked purposely with her head down into the cold October evening. “Hey there, who are you hiding from, came a voice from the shadows.” Morag knew the voice but it didn’t belong here. She stopped in her tracks and felt her heart skip a beat or two. Charlie stepped from the shadows with a smile as wide as the peak on his cap. “Charlie, what are you doing here?” She hugged him tight to the amusement and whistles from her workmates. Charlie explained his father had signed-up and so he was on leave to see him but wanted to surprise his fiancé.

Morag joins the Land Army. The war bought employment opportunities for women and while munitions employed the most women other jobs such as office clerks, public transport workers and even work in shipyards was available. Women were poorly paid compared to men but the experience of work was opening women’s eyes. In October 1917 Morag decided feeding people was better than making weapons and so joined the Women’s Land Army.

Morag longs for warmer weather. Now fully trained to work on the land Morag spends nearly 50 hours a week working on a farm. The work is physically exhausting and she longs for warmer weather. At least now she feels good about her work. Being cold is nothing compared to being cold in a trench while enemy bullets and shells fly overhead; or in a prison cell where John was serving his third sentence for refusing military service.

Spring arrives. The sense of new life arrives on the farm with birdsong in the air, the birth of lambs and wild flowers bursting through hedgerows. Morag marvels at the power of nature compared to mankind’s foolish sense of superiority on the planet and thinks to herself, “We can bomb ourselves into oblivion but the seasons will carry on regardless”.

Morag’s father called to war. The Third Military Service Act of April 1918 extended the age of conscription to 51, which meant Morag’s father, Peter, aged 47 would go to war. Morag, barely over the loss of her brothers, couldn’t believe her father’s enthusiasm to be at the front. If it wasn’t for his wife he would have volunteered already. Now the government had given him what he wanted – a shot at revenge.

Two’s company. With her father away Morag decided to leave her job on the farm to move back in with her mother. The thought of her mother alone in the house was too much for Morag to bear. She was determined not to go back to the munitions factory but by luck found work as a typist at the University College, Dundee. This would prove very fortuitous.

Ambition awakes. There’s a sense that the allies are gaining the upper hand and possibly that the war will soon be over. Being amongst academics Morag here’s new interpretations of the war and appreciates for the first time the complexity of the world. She decides when the war is over that she will fulfil her dream to study for a degree especially as she now knew her subject would be History.

God, don’t let him die!. Over the last 4 years Morag had lost what little religion she started with but when news arrived that Charlie had contracted flu she realised how much she wanted there to be a god so that he might spare Charlie. She wanted their life together. She had lost brothers and friends to the war. It seemed there wasn’t a street in Dundee that hadn’t lost a son or a father. Charlie survived the flu but it would be some months before he was fully recovered.

The war ends. On the 11th November 1918 the war ends. Morag had spent the war as most other women, on the home front trying her best to make ends meet. Selfishly she felt as though life was on hold. Her way to survive while the only news was of death and loss was to hold on to her dreams.

Morag and Charlie marry. Morag wanted to get married in December 1918 but Charlie was to weak from the flu and her father had not returned from France. With so many men awaiting transport home Peter had to wait on his turn. The sun shone that Spring day in 1919 as Morag and Charlie tied the knot. The war had stolen the smile from the face of the boy she met on the tram when she was 15 but she was thankful for what she still had. Charlie caught her eye as he raised a glass to the heavens. She smiled and knew what he was thinking, as she too took a long moment to remember her brothers, lost at Loos.

Fiancée – Morag Anderson

August 1914

Morag faces reality

September 1914

A short goodbye

April 1915

Charlie writes

June 1915

Charlie injured

September 1915

Munitions work

September 1915

Brothers fall at Loos

October 1915

Dundee Rent Strikes

October 1915

The Bellefield Avenue barricade

July 1916

Tired of munitions

September 1916

Morag writes to Charlie about his brother John

October 1916

A surprise at the factory gates

October 1917

Morag joins the Land Army

January 1918

Morag longs for warmer weather

April 1918

Spring arrives

May 1918

Morag’s father called to war

June 1918

Two’s company

August 1918

Ambition awakes

September 1918

God, don’t let him die!

November 1918

The war ends

May 1919

Morag and Charlie marry