Great War Dundee

This is Dundee's story of those that served in the First World War, and of the people left at home

WW1 Cryptography – a Dundee link

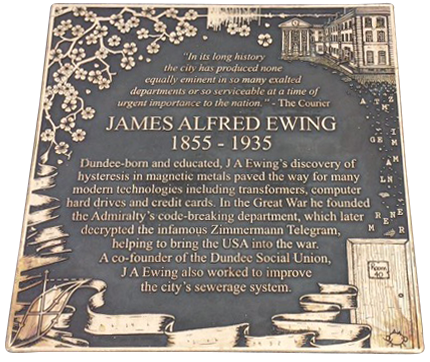

An important weapon of war is the ability to listen in on your enemy’s communications. In 1917 British intelligence officers, of the Admiralty’s Code-breaking department, (headed by James Alfred Ewing from Dundee), intercepted and decrypted a German telegram. The content of the telegram angered America enough to draw them into the conflict. Considered a turning point in the war, the story of the Zimmerman Telegram has roots far back in history.

What is Cryptography?

Cryptography is the science of writing in secret code and has been used by government officials, spies and religious leaders throughout the ages to communicate secret messages. Today cryptography is at the heart of all secure modern communications and protects your privacy whenever you chat to your friends online or log on to secure websites.

So where did it all begin?

For as long as humans have been communicating there’s been the need to hide or protect information. There is physical evidence of this dating back to at least 1500 BC in the form of clay tablets from Mesopotamia containing a craftsman’s coded recipe for pottery glaze. Presumably the recipe was commercially valuable and so worth protecting. Even today the recipe for Coca-Cola is said to only be known by a handful of people so our early days potter knew the value of protecting his invention.

More often though secret or encrypted messages were useful to prevent enemies from knowing each other’s plans. It is believed the Ancient Greeks used ciphers in the form of scytales to communicate during military campaigns. A scytale was a simple strip of parchment with letters which when wrapped around a rod of the correct diameter would reveal the message. The most widely-known of early ciphers is the Caesar Cipher. Named after Julius Caesar, the cipher uses the technique of writing a coded message by simply shifting the alphabet by a consistent number of places. Shifting left by 4 places for example would turn A to E, B to F etc. The encrypted message ‘EXXEGOEXSRGI’ translates to ‘ATTACK AT ONCE’.

Try the Caesar Cipher for yourself below to send encrypted messages to your friends and family. Click the + and – buttons to set a particular shift.

The Babington Plot – a lesson in deception

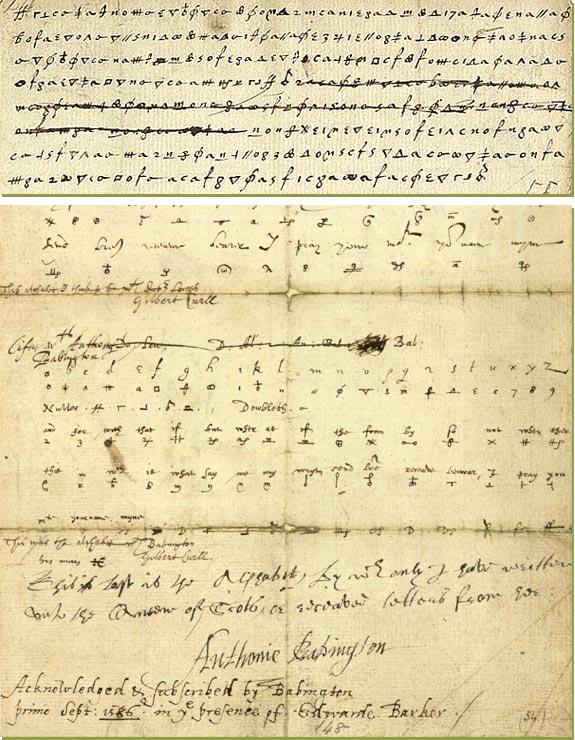

While under permanent house arrest by her cousin Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots conspired in a plot to assassinate Elizabeth. Believing she was communicating with her co-conspirator, Anthony Babington, through a safe cipher, Mary incriminated herself enough to lead to her execution.

The story of the Babington Plot involving state players, spies and double agents, is as intriguing as any cold war spy novel but at the heart of the story is the skill of the cryptanalyst Thomas Phelippes. While Mary believed the message was secure, in reality Babington’s encrypted letter had first been deciphered by Thomas Phelippes using a method called frequency analysis. The cipher included a series of symbols to represent, letters, words and phrases. Phelippes found patterns in the distribution of the symbols and was able to slowly deduce the meaning until eventually much of the letter was decoded revealing Babington’s desire to assassinate Elizabeth. The letter continued its journey to Mary and her response to Babington lead to her execution in February 1587.

Frequency analysis was first documented in the 9th century by Al-Kindi, an Arab polymath and still remains a foundation for codebreaking. In any reasonable length of written language, certain letters and combinations of letters occur with varying frequencies. Those same frequencies will occur in an encrypted text so providing the initial clues to decipher the message. Today frequency analysis can be performed in seconds using computer software and so classical ciphers provide no longer provide real protection.

Room 40, the Dundee connection, and the Zimmerman Telegram

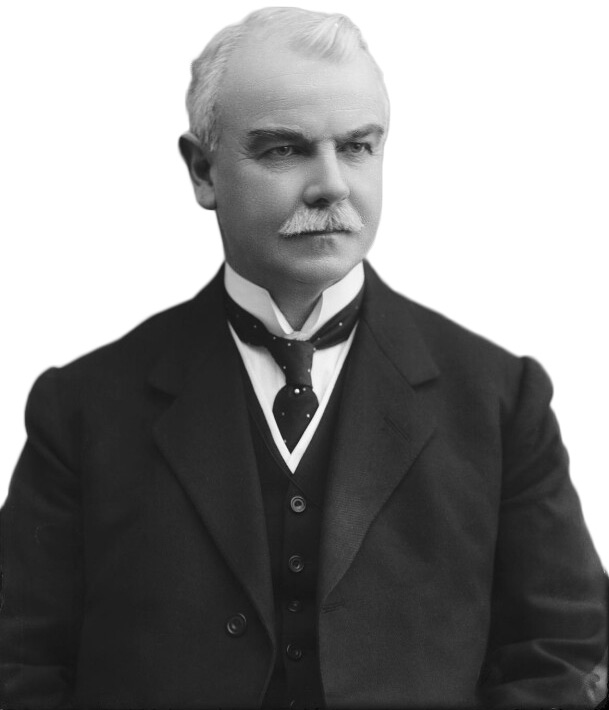

By the First World War ciphers had advanced far beyond the days of Julius Caesar and Mary Queen of Scots and so in 1914 ‘Room 40’, based in Whitehall, was setup as a dedicated intelligence unit. Led by the Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, originally from Dundee, Ewing recruited the best minds of the day on to his elite team of code breakers.

At the start of 1917 the allied forces were impaired by massive losses at the front and were looking to America for support, but America stood firm on remaining neutral. Could a perceived threat from the Germans be enough to draw America into the conflict?

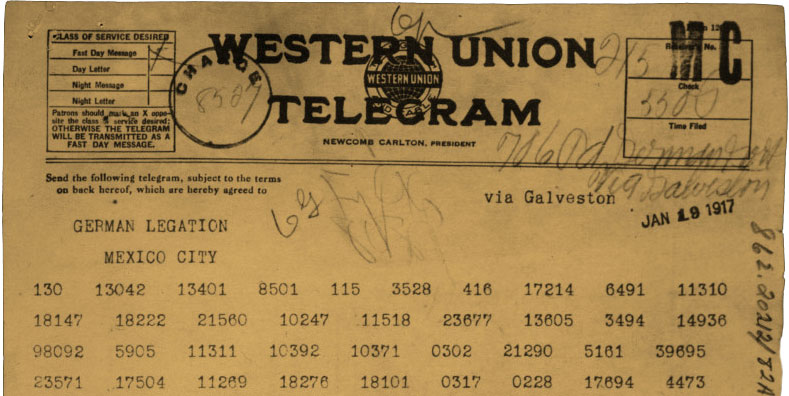

On the evening of 16th January 1917, a British Intelligence officer by the name of Dilly Knox was at his desk in Room 40. Dilly was a classics scholar from Cambridge and among the greatest code breakers of his day. An intercepted coded telegram from the German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, was handed to Dilly which he immediately started work on. His uncanny ability to see patterns in the numbers helped him to slowly decrypt the message and by the following morning he and fellow officer, Nigel de Grey had uncovered an invitation to Mexico to join Germany in the war and in the process Germany would help Mexico to recover Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. Dilly and Grey were convinced the message was of significant importance and so took it to a superior officer, Captain Hall. As the British weren’t ‘officially’ intercepting communications from Germany, Hall devised a plan for the message to reach America’s attention through an alternative route. The plan worked and America responded in April 1917 by declaring war on Germany. Of the 15,000 intercepted communications, the Zimmerman telegram was the standout moment. Described as the most significant intelligence triumph for Britain during World War One, it changed the course of the war and almost definitely ensured victory over Germany and the Central Powers.

Modern day cryptography

In order for an encrypted message to be read the recipient must know how to decrypt the message. This was relatively easy with the early ciphers such as the Caesar Cipher. Knowing how to decipher a message is both its strength and weakness. Once the key to deciphering the message falls into the wrong hands the cipher is useless. By the time of the Zimmerman intercept the recipient required a code book to enable them to decipher the message. Several of these were acquired by intelligence services enabling them to decode intercepted messages and to more easily break updates to the German cipher.

With the advent of the computer age and the transmission of messages between devices the requirement for encryption is no longer just for passing secret messages. The miracle of the internet has delivered global communications to us all. Today we can do almost anything on devices the size of our hand; from ordering a pizza, talking to our friends, through to running our finances. Almost everything we do online will be encrypted. Without encryption, we are vulnerable to our personal data falling into the wrong hands.

So how does it work? Modern cryptology relies on complex algorithms to make it nigh on impossible to decrypt a communication without the recipient having the key to do so. Dilly Knox from 1917 would be lost forever staring at a screen of meaningless characters. But just as it has been throughout history there’s value in breaking secret messages, and digital age encryptions do get broken, but unlike the past, today we’re all targets. Rest assured though the technology companies we rely on work hard to keep ahead of the bad guys; their reputations depend on it.