Great War Dundee

This is Dundee's story of those that served in the First World War, and of the people left at home

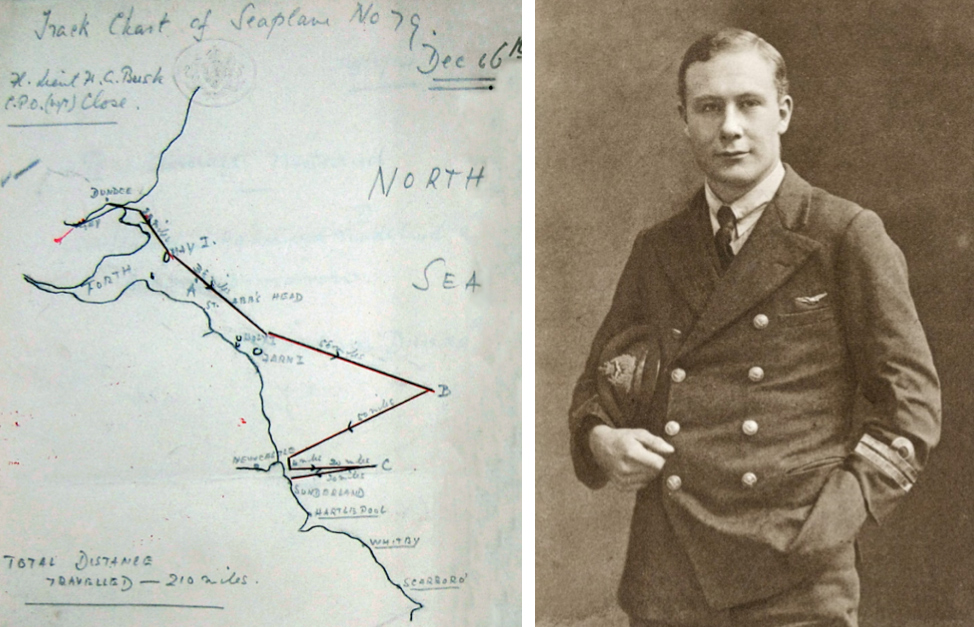

North Sea Patrol. Royal Naval Air Station Dundee

The seaplane tender HMS Hermes arrived in September 1913 to evaluate the Tay’s suitability as a naval aviation base. The trials, which included Lieutenant Arthur Gaskell flying from Broughty Ferry to the Tay Bridge at an astonishing 56 MPH, were a success and Royal Naval Air Station Dundee opened at Stannergate on 9 February 1914. Major Robert Gordon of the Royal Marines flew in the first ‘hydro-aeroplane’ that same afternoon and the first landplane landed a few days later on a hastily cleared runway next to Broughty Ferry Road.

Aircraft from RNAS Dundee carried out long, bitterly cold and often boring patrols along the east coast shipping route and anti-submarine operations far out into the North Sea. One notable airman to pass through RNAS Dundee was Flight Lieutenant Frederick Rutland who, along with Lieutenant Commander Charles Robinson, took off in a Short 184 seaplane on 7 March 1916 to join the seaplane tender HMS Engadine. Three months later, at the Battle of Jutland, Rutland would make history by flying the first reconnaissance mission to spot enemy warships during a fleet action. Later still, between the wars, he would win fame of a very different sort by becoming a Japanese spy.

Another famous airman to fly from Dundee was Major Christopher Draper who would often relieve the boredom of long convoy patrols by flying through arches of the Tay Bridge. Draper, whose bridge escapades earned him the nickname ‘The Mad Major’ would also become a spy, only this time for the British intelligence services!

On the evening of 2 April 1916, Dundee’s seaplanes were briefly, and rather embarrassingly, thrust into the front line of the first blitz on Britain. Zeppelin airships had been spotted crossing the North Sea towards the Firth of Forth that afternoon and Flight Commander Tom Elston, commanding officer at RNAS Dundee, ordered three Wight seaplanes prepared for take-off.

Wight seaplanes, so named because they were built on the Isle of Wight, were torpedo bombers and were not fitted with guns. But the Dundee crews armed themselves with revolvers, rifles loaded with .303 incendiary ammunition and Ranken explosive darts, missiles designed to be dropped from above an airship, penetrate the fabric covering, then detonate inside. Commander Elston was, however, keenly aware that the woefully underpowered Wight seaplane’s rate of climb was so poor, there was very little chance they would ever be able to intercept the enemy airships, let alone gain sufficient height to use the Ranken darts.

The order to take off finally came through at 9.15 p.m. but nothing could be done as it was then low tide and the bottom of the launching slipway was well clear of the water. Two aircraft were eventually launched an hour later, but both hit trouble before getting airborne, one suffering engine failure, the other colliding with an unlit buoy, and their crews had to spend a very cold night drifting up and down a fog-bound River Tay.

The two Zeppelins were able to bomb Leith and Edinburgh unhindered, killing 13 people, injuring another 24 and causing considerable damage. One direct result of this raid and the inability of the Dundee seaplanes to respond, was the building of a new airfield at Turnhouse Farm on the western outskirts of the capital. That airfield is better known today as Edinburgh Airport.

RNAS Dundee originally had two seaplane sheds, rising to four by 1918 with an additional slipway capable of handling larger flying boats and a hutted camp beside Craigie Drive. The wardroom and officers’ accommodation were at The Wyck, an art nouveau villa also off Craigie Drive and the only station building that survives a century on. In 1918, RNAS Dundee was used as an ‘acceptance station’ to which new seaplanes were delivered for testing. The station closed in 1919, but was reactivated in the Second World War as HMS Condor II, a satellite of HMS Condor at Arbroath.